TBOTB Blog sponsored by: Protalus

Rimming the northern tip of Tal’Afar, along route Sante Fe, between checkpoint 101 and checkpoint 201 was a slight slope, or incline in the terrain that was steep enough that you couldn’t quite see up and over the hill. As you approached its apex, the rest of the route easily became visible; it was at that very pinnacle that there was a concrete house on the corner of a small road that jutted out nearly to the road. The entire right-hand side (or south side of the road, as it would be) was a long series of Tal’Afar neighborhood homes, but this one seemed to have been built extremely close to the road. We called it “the shoot house.” We called it that because it was abandoned, but due to its popular location almost at the top of the grade of the hill, and on the corner of that narrow street, it was the perfect place to shoot at American convoys going up and down route Sante Fe.

A very grainy photo of ‘the shoot house’ circa December, 2004

You easily could initiate a small arms ambush, or trigger an IED and then skulk away into the back alleys and courtyards of the neighborhood. And often times that is exactly what happened. It was the location of a coordinated ambush that hit my platoon one night when we were tasked with escorting an engineer company out of town; the IED and corresponding small arms fire disabled the Stryker in front of me, my lead vehicle, forcing us to drift to a halt right in the middle of ‘the kill box.’ Thankfully we had superior firepower as compared to the RPG’s and small arms of the insurgents, and my men were only lightly wounded.

But it was for this reason that when given the chance at an opportunity, our Squadron was more than happy to oblige. As a whole, the Squadron had its fill of the shoot house being used for nefarious purposes. One sunny day in Iraq, word came down that we could have use of an Air Force asset that had been relocated to the AOR for two weeks: The AC-130 Spectre gunship, or “Spooky.” As there were rules of war, we couldn’t just shoot any-old-thing around Tal’Afar, so the shoot house was put forward as one nomination for a target package. At the end of the day, the shoot house won out.

AC-130 ‘Spectre’ Gunship on display at the U.S. Air Force museum, Dayton, OH.

But, as there were laws of war and what have you, we were required to attempt to locate any legitimate owner of that home; we already knew that the shoot house and its surrounding five homes were all dilapidated and abandoned, but still had to at least make it look like we were making an effort. And then we had to ensure that no Iraqi civilians were going to be in or around the premises the night the operation was scheduled to take place. So Civil Affairs devised some IO fliers that essentially said “it is dangerous at night so don’t go near this house on Tuesday night” (or something to that effect). They also came up with some pretty cool ones in the line of “There’s a red-eyed dragon in the skies at night. Obey curfew of it might spit its fire at you.” I thought that was pretty cool, but in order for the IO to be successful, you had to show them that there was actually a dragon.

And on the night in question, Spooky did just that. It had been circling Tal’Afar all week late in the evening, or early hours of the morning, looking for blatant targets of opportunity (or if there were U.S. troops in contact). But the night had finally arrived for the show of force. I wasn’t sure how people were to see it, unless they could do so from the courtyard or roofs, once they heard the commotion and if they dared emerge from their homes.

Spooky rained-down precision fire on the shoot house, spitting red tracers from its cannons and guns. Anyone who would’ve seen that display of power surely would have given serious thought about violating curfew – even if they were just going to a neighbor’s house for tea, and not running around town planting IEDs.

After that day we stared calling it the Swiss-Cheese house. You’d get occasional activity, but no one really was able to use it as trigger or ambush points again. Funny how some stuff sticks.

“Oh, you want to go to the Housaniya neighborhood? Well, go up Sante Fe to the Swiss-Cheese house, then turn right…can’t miss it.”

Discount Code: ffvillage

Discount Code: ffvillage

Code:

Code:

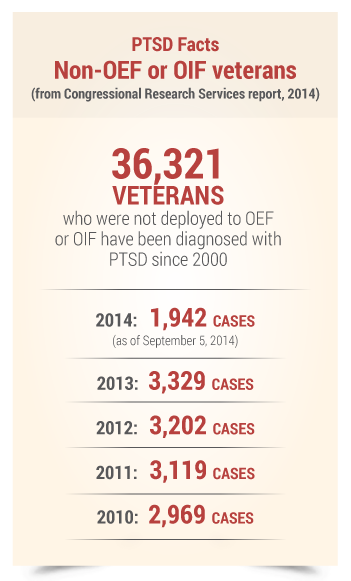

of the DSM-V and extensive clinical experience in diagnosing and treating veterans with PTSD. Persons with the requisite professional qualifications include board-certified psychiatrists and licensed psychologists, as well as psychiatric residents and psychology interns under the close supervision of an attending psychiatrist or psychologist.In addition, the diagnosis must conform to the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-V.

of the DSM-V and extensive clinical experience in diagnosing and treating veterans with PTSD. Persons with the requisite professional qualifications include board-certified psychiatrists and licensed psychologists, as well as psychiatric residents and psychology interns under the close supervision of an attending psychiatrist or psychologist.In addition, the diagnosis must conform to the diagnostic criteria in the DSM-V.

The VA Adjudications Procedures Manual M21-1MR (available on the

The VA Adjudications Procedures Manual M21-1MR (available on the

For the veteran’s service records to corroborate the stressor, they do not need to include every detail of the event. If there is independent evidence of the occurrence of a stressful event and that evidence shows the veteran’s personal exposure to the event, that could be sufficient corroborative evidence.

For the veteran’s service records to corroborate the stressor, they do not need to include every detail of the event. If there is independent evidence of the occurrence of a stressful event and that evidence shows the veteran’s personal exposure to the event, that could be sufficient corroborative evidence.