TBOTB Blog proudly sponsored by: wwwprotaluscom: Discount code ffvillage

Support Wounded Warriors Publishing

Question- d.hardt@protalus.com – Write for us!

Stay Tuned for Wednesday Blog: Secondary Service Connection.

In the previous post on Combat-Related Special Compensation (CRSC), we discussed the first part of qualifying for CRSC: the criteria for Military Retirement. In this post, we will talk about the second part: what qualifies as “combat-related”.

Dual Criteria for Eligibility for CRSC

In order to qualify for CRSC, the veteran has to prove that his/her case satisfies two requirements:

-

The veteran has to meet the Military Retirement criteria

-

The veteran’s disability has to be both VA service-connected and considered to be “Combat-Related”

It is important to stress that CRSC Board (which is responsible for determining and awarding CRSC) will only consider disabilities that have already been service-connected by the VA at a 10% minimum rating. This means that if a veteran has been awarded service-connected for a disability, but at 0% (which does happen), the veteran would not be eligible for CRSC until the VA awards a higher rating for that disability.

Combat-Related Disabilities

For the purposes of CRSC, the Department of Defense (DOD) has determined that combat-related disabilities may have occurred in the following instances:

-

Direct result of armed conflict

-

Instrumentality of war

-

Performance of duty under conditions simulating war

-

Engaged in hazardous service

-

Purple Heart disability

In addition to the five categories above, the DOD has identified two other instances where disabilities could be considered for CRSC purposes:

-

Presumptive conditions

-

Secondary conditions

While the DOD gives multiple instances in which disabilities can qualify as combat-related, it is important to note the CRSC Board only needs to conclude that the disability falls within one of the categories of combat-related disabilities. Proving that a disability satisfies more than one category has no impact on the CRSC Board.

Disabilities Incurred as Direct Result of Armed Conflict

According to the DOD, “armed conflict” includes any action in which service members are engaged with hostile forces. “Armed conflict” may also include any period of time during which a service member:

-

Was a prisoner of war

-

Detained against their will in the custody of a hostile or belligerent force

-

Escaping, or attempting to escape from such confinement.

Disabilities Incurred Through an Instrumentality of War

An instrumentality of war is a vehicle, weapon or device designed primarily for military service and intended for use in such service at the time of the occurrence or injury. Such disabilities could include wounds, injuries or illnesses caused by:

-

Military weapons

-

Combat vehicles

-

Fumes & gases

-

Explosions of military ordnance, vehicles, or material

An instrumentality of war can also be an object, device, vehicle, etc. that is not specifically designed for military purposes, but that is situationally being used to simulate war activities. An example of this would using a broomstick instead of a pugil stick for hand-to-hand combat training.

Disabilities Incurred in the Performance of Duty under Conditions Simulating War

This combat-related category includes disabilities that result from military combat training. Examples of this include:

-

War games

-

Practice alerts

-

Tactical Exercises

-

Airborne operations

-

Leadership reaction courses

-

Grenade and live fire weapons practice

-

Bayonet training

-

Hand-to-hand combat training

-

Rappelling

-

Negotiation of combat confidence and obstacle courses

Note: For the purposes of CRSC, military training does not include physical training activities such as calisthenics, jogging, formation running, or supervised sport activities.

Disabilities Incurred While Engaged in Hazardous Service

According to the DOD CRSC Guidance Program, hazardous service includes, but is not limited to:

-

Aerial flight

-

Parachute duty

-

Demolition duty

-

Experimental stress duty

-

Diving duty

Purple Heart Disabilities

In order to obtain CRSC for Purple Heart disabilities, two things are required:

-

The disability must be service-connected by the VA

-

The disability must the result of an injury for which the veteran was awarded the Purple Heart

Verification that the Purple Heart was awarded can be found in various military documents, including:

-

DD 214

-

Purple Heart Certificate

-

Military orders for the award of a Purple Heart

Note: The award of a Purple Heart does not by itself prove that a particular VA service-connected disability qualifies as “combat-related”. The veteran still needs to provide proof that the disability for which he/she is seeking CRSC was the result of the injury for which the veteran was awarded the Purple Heart. Such proof might include service medical records describing the incident, or the Purple Heart certificate itself if it describes the incident with sufficient clarity.

Discount Code:

Discount Code:

Code:

Code:

The annoying sound of a cow alarm clock going off a couple of rooms down awakes me out of my sound sleep. I toss over in my bed, putting a pillow over my head trying to drown out the ringing. “Crap, is it that time already?” I clear the bird poop out of my eyes and glance at my faithful watch; it blares 5:50 a.m. I languorously roll out of bed. Unexpectedly Bill, who lives on the top bunk, already has gotten a jump on the day. It’s the day that everyone has been waiting for: our progressive offensive move into a city that we know little about. The one thing that is guaranteed: They know we are coming; they always do.

The annoying sound of a cow alarm clock going off a couple of rooms down awakes me out of my sound sleep. I toss over in my bed, putting a pillow over my head trying to drown out the ringing. “Crap, is it that time already?” I clear the bird poop out of my eyes and glance at my faithful watch; it blares 5:50 a.m. I languorously roll out of bed. Unexpectedly Bill, who lives on the top bunk, already has gotten a jump on the day. It’s the day that everyone has been waiting for: our progressive offensive move into a city that we know little about. The one thing that is guaranteed: They know we are coming; they always do. It’s similar to a high school scenario. A kid gets into a fight on the other side of the school, and before you know it, friends have shown up, and the fight now has an audience. The world of technology in this region has improved just enough to make things difficult for our surprises or an offensive or whatever it may be.

It’s similar to a high school scenario. A kid gets into a fight on the other side of the school, and before you know it, friends have shown up, and the fight now has an audience. The world of technology in this region has improved just enough to make things difficult for our surprises or an offensive or whatever it may be. Our first stop before our push into the fight was midpoint camp. We settled in and started the planning and prepping. The good thing about Camp Kelso is it doesn’t get hit a lot by mortars or rockets, but since the whole world had just witnessed the task force making its way in during the middle of the day, we all knew that where the circus goes so do the clowns. Back in a tent, just like when we were at FOB Falcon. The first night, as we sat in the tent and relaxed, what sounded like a whistle going off was heard. Everyone was silent. I looked over at Staff Sergeant Pearson. The look on his face gave me the impression that something was up. He looked around and said, “That didn’t sound right.” Booooom. The ground moved like an earthquake. Everyone jumped up and made their way to the bunker. Booooom. I didn’t have socks on, so as I made my way to the bunker, I found myself with sharp rocks pricking at my feet. We huddled in the bunker, and everyone was talking about how close the rockets sounded and what they were doing when it went down.

Our first stop before our push into the fight was midpoint camp. We settled in and started the planning and prepping. The good thing about Camp Kelso is it doesn’t get hit a lot by mortars or rockets, but since the whole world had just witnessed the task force making its way in during the middle of the day, we all knew that where the circus goes so do the clowns. Back in a tent, just like when we were at FOB Falcon. The first night, as we sat in the tent and relaxed, what sounded like a whistle going off was heard. Everyone was silent. I looked over at Staff Sergeant Pearson. The look on his face gave me the impression that something was up. He looked around and said, “That didn’t sound right.” Booooom. The ground moved like an earthquake. Everyone jumped up and made their way to the bunker. Booooom. I didn’t have socks on, so as I made my way to the bunker, I found myself with sharp rocks pricking at my feet. We huddled in the bunker, and everyone was talking about how close the rockets sounded and what they were doing when it went down.

Code:

Code:

Once a veteran’s PTSD has been service-connected, a disability rating will be assigned by the VA. A disability rating is the average impairment in earning capacity resulting from diseases, injuries, or their residual conditions. It is important to note that C&P examiners do not rate claims; exam results go to a VA adjudicator to apply the rating formula and provide a rating for the veteran’s PTSD.

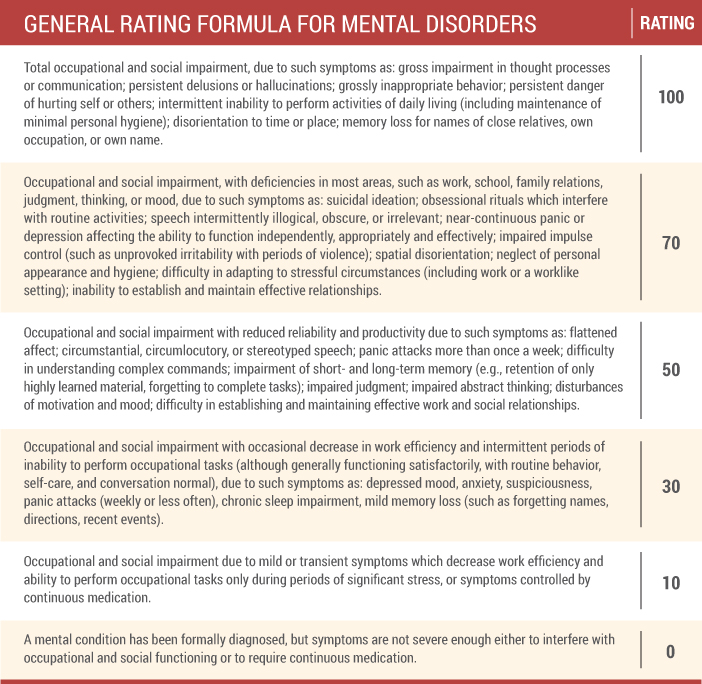

Once a veteran’s PTSD has been service-connected, a disability rating will be assigned by the VA. A disability rating is the average impairment in earning capacity resulting from diseases, injuries, or their residual conditions. It is important to note that C&P examiners do not rate claims; exam results go to a VA adjudicator to apply the rating formula and provide a rating for the veteran’s PTSD. The VA rating formula goes from zero percent to 100 percent, in increments of 10, but not every disability includes each rating percentage. For example, a veteran’s PTSD can be rated at 0, 10, 30, 50, 70, or 100 percent debilitating. A zero percent rating means that “a mental condition has been formally diagnosed, but symptoms are not severe enough either to interfere with occupational and social functioning or to require continuous medication.” A 100 percent rating is warranted when there is “total occupational and social impairment” due to specified symptoms. Most veterans fall somewhere in the middle.

The VA rating formula goes from zero percent to 100 percent, in increments of 10, but not every disability includes each rating percentage. For example, a veteran’s PTSD can be rated at 0, 10, 30, 50, 70, or 100 percent debilitating. A zero percent rating means that “a mental condition has been formally diagnosed, but symptoms are not severe enough either to interfere with occupational and social functioning or to require continuous medication.” A 100 percent rating is warranted when there is “total occupational and social impairment” due to specified symptoms. Most veterans fall somewhere in the middle.

As you can see in the chart above, symptoms that the VA considers when rating PTSD include, but are not limited to: impairment in thought processes or communication, grossly inappropriate behavior, persistent danger of hurting self or others, suicidal ideation, intermittent inability to perform activities of daily living (including maintenance of minimal personal hygiene), memory loss, panic or depression affecting the ability to function, impaired impulse control, chronic sleep impairment, and decreased work efficiency.

As you can see in the chart above, symptoms that the VA considers when rating PTSD include, but are not limited to: impairment in thought processes or communication, grossly inappropriate behavior, persistent danger of hurting self or others, suicidal ideation, intermittent inability to perform activities of daily living (including maintenance of minimal personal hygiene), memory loss, panic or depression affecting the ability to function, impaired impulse control, chronic sleep impairment, and decreased work efficiency. During its evaluation, the rating activity must consider the frequency, severity, and duration of psychiatric symptoms; the length of remissions; and the veteran’s capacity for adjustment during periods of remission. The rating should be assigned based on all evidence in the record which relates to a veteran’s occupational and social impairment, but a rating cannot be assigned based solely on social impairment. Remember that the purpose of VA disability benefits is to compensate veterans for impairment in earning capacity. Therefore, it is important to emphasize how a veteran’s PTSD symptoms have impaired his or her ability work and maintain gainful employment. If a veteran is unable to work due to his or her PTSD, he or she may be eligible for total disability based on individual unemployability (TDIU). TDIU is another way to get to a 100 percent disability rating if a veteran’s PTSD does not warrant a 100 percent schedular rating but he or she is still unable to obtain and maintain substantially gainful employment.

During its evaluation, the rating activity must consider the frequency, severity, and duration of psychiatric symptoms; the length of remissions; and the veteran’s capacity for adjustment during periods of remission. The rating should be assigned based on all evidence in the record which relates to a veteran’s occupational and social impairment, but a rating cannot be assigned based solely on social impairment. Remember that the purpose of VA disability benefits is to compensate veterans for impairment in earning capacity. Therefore, it is important to emphasize how a veteran’s PTSD symptoms have impaired his or her ability work and maintain gainful employment. If a veteran is unable to work due to his or her PTSD, he or she may be eligible for total disability based on individual unemployability (TDIU). TDIU is another way to get to a 100 percent disability rating if a veteran’s PTSD does not warrant a 100 percent schedular rating but he or she is still unable to obtain and maintain substantially gainful employment.